Mongolian Music Instruments are extremely diverse, traditional Mongolian folk music is influenced by a variety of tribes, which were combined for the first time in the 13th century under Genghis Khan's authority with Turkish tribes to become the Mongolian people. Over a long period of time, nomadic Mongolians created a diverse range of musical instruments, elaborated music playing techniques, and established a rich repertoire for those instruments. String instruments, wind instruments, and percussion instruments are the three types of Mongolian national music instruments in terms of sound. The ancient Mongolian nomadic livestock herders and hunters dedicated their musical instruments to themselves or to nature.

Mongolian String Instruments

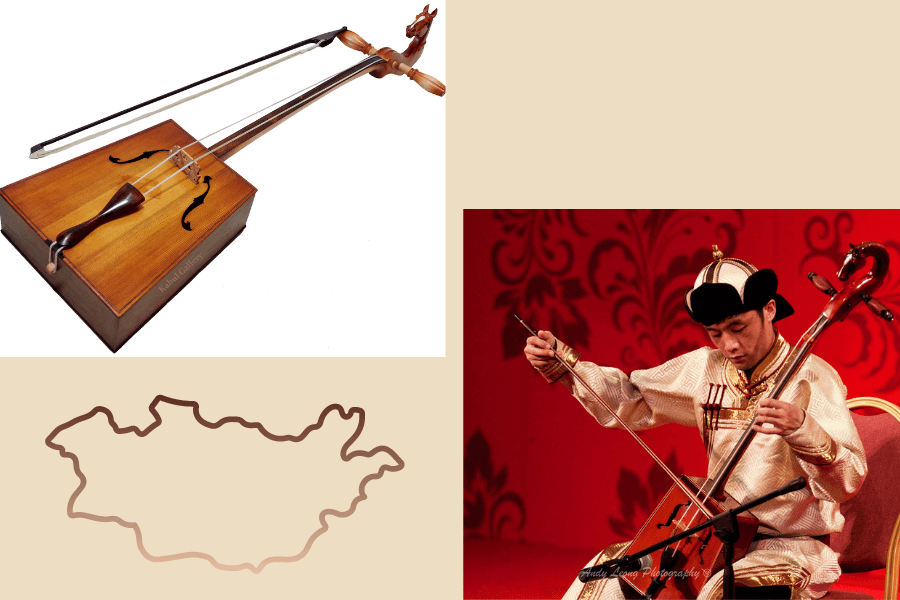

Morin Khuur (Horse-Head-Violin)

The Morin Khuur is a traditional two-stringed Mongolian music instruments. Both the body and the neck are made of wood. The neck is shaped like a horse's head, and the sound is similar to that of a violin or cello. The strings are constructed of dried sinew from deer or mountain sheep. It is played with a willow bow that has been strung with horsetail hair and coated with larch or cedar wood resin.

This instrument is used to play polyphonic tunes since the melody and drone-strings can be played simultaneously with a single stroke of the bow. The Horeshead Violin is the most common instrument in Mongolia, and it is used to accompany dances and songs as well as during celebrations and rites. The hu can even simulate the sound and noises of a horse herd.

There is a legend about the creation of this instrument. A Mongol missed his dead horse so much that he built an instrument out of its head, bones, and hair and began to reproduce the familiar tones of his beloved steed. This instrument's history is based on previous legends. That a shepherd acquired a magical horse with the ability to fly as a gift from his beloved woman. He flew it at night to meet his beloved. His envious wife severed the horse's wings, causing the horse to fall from the sky and perish. From his beloved steed, the bereaved shepherd fashioned a horse-head violin.

Shanz (Shant or Shudraga)

The chant's initial appearance is a very long neck with sharp spikes connected to a flat oval body-resonator coated in snake skin, according to folklore. Three silk or residential strings provide a rattling, rustling, somewhat banging sound. The shudraga, also known as the shant, is a long-necked spiked lute with an oval wooden frame and snake skin covering spread across both faces. The three strings are attached to a bar that is embedded in the body. The instrument is struck or plucked with a horn plectrum or with the fingers. Because the tones do not echo, each note is struck multiple times.

The Mongol chance is also known as sudraga. Shudrag or shant was popular during the reign of Khan Ugedei. One of the Persian texts mentions a shant played in Haana Togoontumur's palace. "She was known as Shidurgui. The shudrag got its name from the way the strings looked to tug or from the length of the instrument's neck. Shudraga was another name for the Mongol bucket.

A shudrag is compared to a lovely girl by Mongols. That is why the appearance of practically all stringed instruments, such as chanz, shanagan huur, yatga, and huuchir, is related with legends involving beautiful Mongolians. "Shanz has a really beautiful melodic voice that can be compared to a flirting girl," some performers say. It has the ability to penetrate a person's soul."

Khun Tovshuur (Tovshuur)

The khun tovshuur is a two or three strung instrument related to Tuva, Altai, and Kazakhstan lutes. The body and neck are carved from cedar wood, and the body is frequently clothed in wild animal, camel, or goat leather. The neck's head is shaped like a swan. Because all tovshuur are handcrafted, the materials and shape of the tovshuur differ based on the maker and location. Depending on the tribe, the string could be constructed of horsehair or sheep intestine, for example. The tovshuur's body is bowl-shaped and normally coated in tight animal hide. There are several instruments that are extremely comparable in the surrounding autonomous areas and neighboring nations. such as the dombra, Kalmykian tovshuur, or Russian balaleika

This traditional instrument was used by the West Mongols to accompany "tuuli" (heroic-epic myths) and "magtaal" (praise songs). The topshur is strongly linked to Western Mongolian folklore and accompanied storytellers', singers', and dancers' performances. The Mongols, according to Marco Polo's descriptions (who traveled through Asia along the Silk Road), also played the instruments before a battle. According to Mongol folklore, they are descended from a swan. The strings are made of horsetail hair and tuned to a fourth interval.

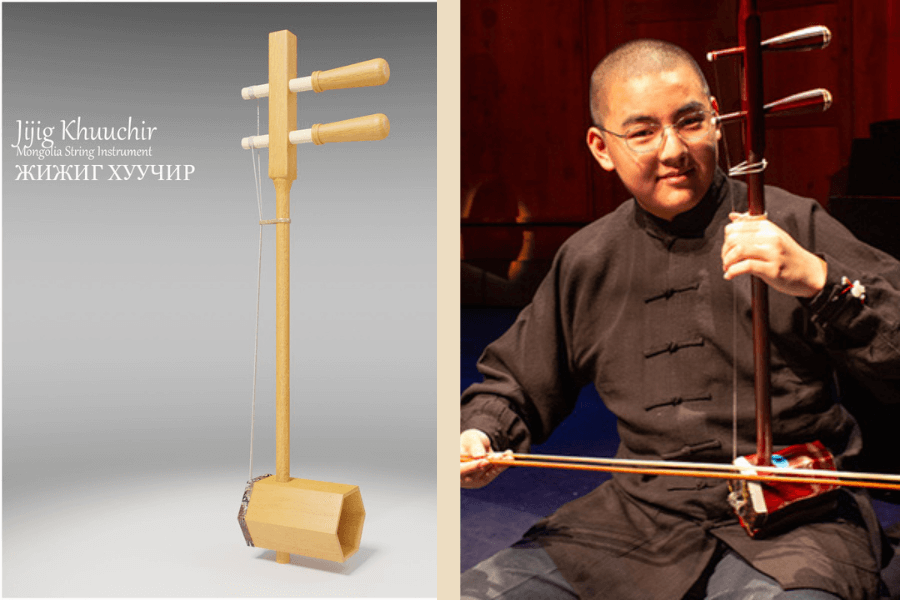

Khuurchi (Erhu)

The khuuchir is a Mongolian music instruments with bowed. Previously, nomads primarily used snake skin or horsetail violins. It is little or medium in size and tuned in the fifth interval. The khuuchir has a small cylindrical, square, or cup-shaped resonator made of bamboo, wood, or copper that is covered with snake skin and open at the bottom. The neck is put into the instrument's body. It typically contains four silk strings, the first and third of which are tuned in unison and the second and fourth in the higher fifth. The bow is covered with horsetail hair and is inextricably linked to the string pairs, in Chinese, this is known as "sihu," which means "having four ears."

The khuuchir can be traced back to more than a thousand years to instruments introduced into China. It is thought to have descended from the xiqin. The xiqin is thought to have originated with old nomadic Hu-people, notably the Xi tribe, who resided on the outskirts of ancient Chinese dynasties. The term huqin literally means "instrument of the Hu people," implying that the instrument originated in regions of ancient China's north, west, or northeastern extremities, which were generally inhabited by nomadic people on the outside of historical Chinese dynasties.

Yoochin (Yangqin)

Dulcimer with 13 double-wire strings in a box. Two wooden sticks, dubbed "little wooden hammers," are used to strike the strings. It has a black wooden soundboard that is elaborately ornamented. The instrument was solely known to locals, and they were the only ones who played it. The bamboo beaters with rubber or leather heads are used to play the yangqin. Its trapezoidal hardwood body is strung with many courses of strings on four or five bridges. The strings on each bridge are tuned full steps apart, while the strings on adjacent bridges are pitched a fifth apart; this arrangement allows a performer to play a chromatic scale in all keys.

Initially, the yoochin was only played in cities. It is most likely from the Persian region. Yangqin has been known in China since the Ming Dynasty. Traditional instruments with three or more bridge courses are still regularly used. Two lightweight bamboo beaters (also known as hammers) with rubber tips are used to strike the instrument's strings. A professional musician would frequently carry several sets of beaters, each of which draws a slightly different tone from the instrument, similar to how Western percussionists use drum sticks. The yangqin is utilized as a solo instrument as well as in ensembles.

Historians provide numerous theories to explain how the instrument arrived in China, including: The instrument could have arrived by land along the Silk Road. It was introduced by sea, via the port of Guangzhou (Canton). Or that it was created by the Chinese themselves, free of foreign influence. Another belief is that the yangqin first met the Chinese via the Silk Road from Mongolia. The Silk Route runs about 5,000 miles from China to the Middle East, including Iran (Persia). The Iranian santur, or dulcimer, has been around since antiquity. If any dulcimer were to have an impact on China via land, it would most likely be this Mongolian music instruments.

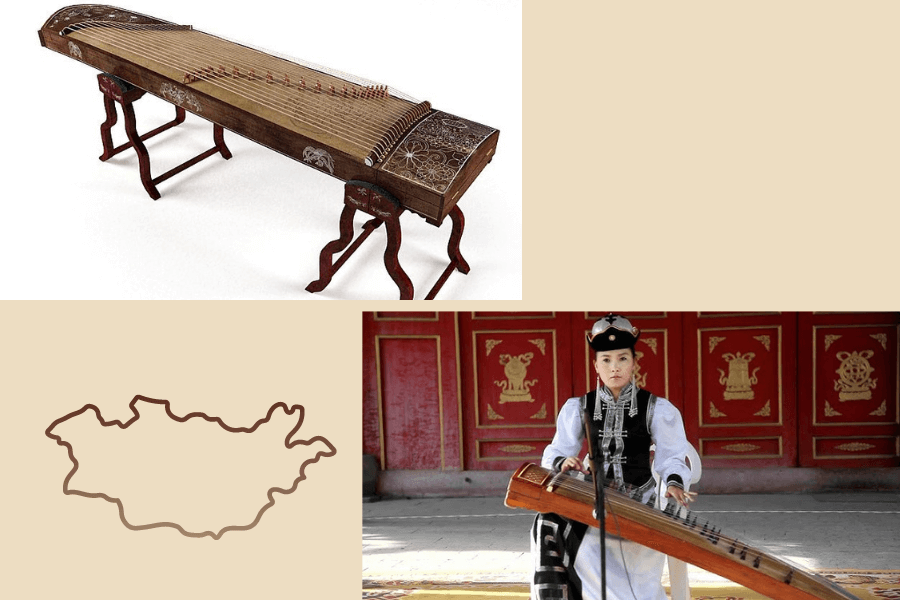

Yatga (Yatuga)

The yatga is a movable bridge half-tube zither. It is built in the shape of a box with a convex surface and one end bent towards the ground. The strings are plucked, and the sound is silky. The instrument was regarded sacred, and playing it was a rite fraught with taboos. Because strings represented the twelve levels of the royal hierarchy, the instrument was mostly played at court and in monasteries.

Shepherds were not allowed to play the twelve-stringed zither, but they could play the ten-stringed zither, which was also employed for interludes during epic recitations. Mongolians traditionally play three variants of this zither, distinguished by their resonators or hollow bodies that amplify the sound. The master yatga; ikh gariing yatga, master yatga with 21 strings (ikh gariing yatga), the national yatga; akhun ikh yatga, and the harp, known as the bosoo yatga are all designs.

The Yatga were the ancestors of the Guzheng. The twelve-stringed variant was historically employed at the royal court for symbolic purposes; the twelve strings equated to the twelve levels of palace hierarchy. The commoners were forced to perform on a 10-stringed yatga. The court and monasteries were the only places where the 12-stringed variant was used. Janggar, a traditional Mongolian epic, tells the account of a young princess who once played an 800-string yatga with 82 bridges; she is said to have only played on the seven lowest bridges.

Mongolian Wind Instruments

Tsuur

The tsuur is a Mongolian wind instrument (flute) made of uliangar wood (bur chervil - umbellifer). Melody and sound are reminiscent of the River Jeven's cascade. The finger has only three holes in it. The blowing technique employs the same teeth, tongue, and lips as Ney in Classical Persian music. Before playing, the Tsuur is frequently dipped in water to seal any leaks in the wood. The tunes played on the Tsuur are mainly imitations of water sounds, animal cries, and birdsongs heard by shepherds on the Altai steppes or mountain slopes.

It is primarily utilized by the Altai Uriankhai people in western Mongolia, while other ethnic groups such as the Kazakhs and Tuvans are known to play or have played it. As previously stated, one of the tunes, "The flow of the River Eev," is named after the river where the sound of khöömii is thought to have originated. The Uriangkhai referred to the Tsuur as the "Father of Music." In the 18th century, a three-holed pipe was used in Mongolia and was thought to have mystical abilities that could bring Lamb's bones back to life. The Tsuur is reported to have had a swan-like voice in the 14th-century Jangar epic.

In 2009, Mongolian Tsuur music was included to the List of Intangible Cultural Heritage in Urgent Need of Protection.

Limbe

The LIMBE is a transverse Mongolian flute. Originally made of bamboo or wood, it is now largely made of plastic, particularly those imported from China. These flutes (transverse flutes) are inextricably linked with Central Asian nomads. The limbe is 65 cm long and contains 9 holes. It is frequently played with circular breathing. The limbe's sound is said to reflect the sounds of nature and is intimately associated with nomadic culture; the sound reflects what is heard in nature or the sounds of the natural and social world. It is frequently used as an accompaniment instrument, although it can also be used for solos in folk music.

Limbe playing is distinguished by euphonious melodies, melisma, hidden tunes, and deft and delicate finger and tongue movements. The frequency and scope of this traditional element's practice are currently unstable, with only fourteen Limbe practitioners left.

Archeological data, historical literature, and ancient sources all reveal that the ancient Huns frequently utilized musical instruments such as the bagpipe, reed pipe, trumpet, and tongue fiddle during their celebrations and religious rituals. From the third to the first centuries B.C., Mongolians began to play the limbe (transverse reed pipe). The discovery of a Mongolian guy playing limbe in a photograph of a Yuan Dynasty musical troupe proves that limbe was commonly utilized throughout the Khubilai Khaan period or Yuan Dynasty.

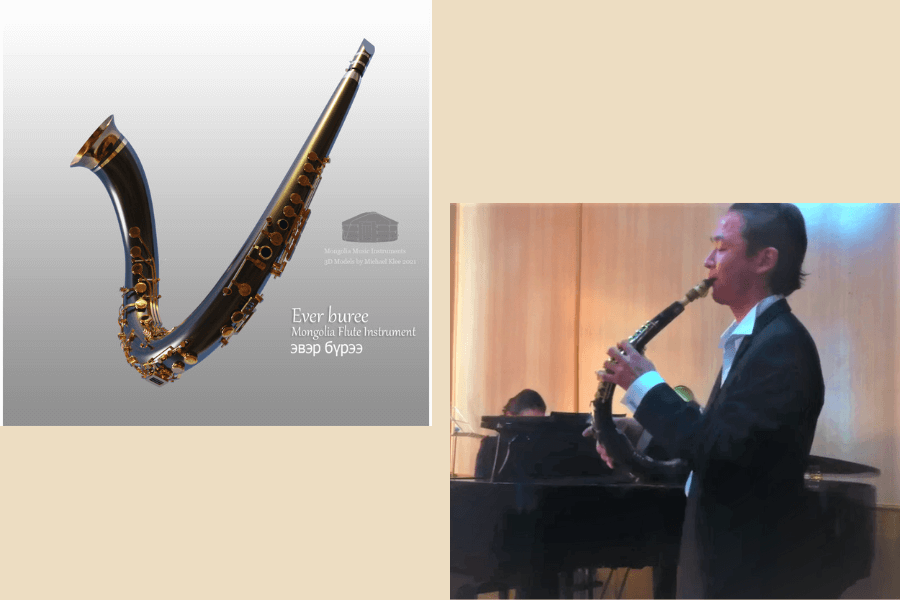

Surnai (Ever Buree)

The ever buree is a Mongolian music instruments that look like a clarinet. Despite its name, which translates as "horn - trumpet," it has the sound of a basset horn (a curved clarinet). Reed instrument - a folk oboe with a conical wood or horn body that widens towards the end. There are seven finger holes and one thumbhole on it. A metal staple holds the reed and a funnel-shaped lip-disc. The short form of the instrument is "haidi," which means "sea flute."

In terms of structure, it is a nearly cylindrical tube made of black ebony that has been curled in a round fashion to allow the instrument's bell to slip underneath the player's right arm. At the upper end of the tube, a mouthpiece (typically a saxophone mouthpiece) with a single reed is attached. The keywork is composed of brass and resembles the German Oehler system in that it uses rollers to move from one key to the next. It, like all clarinets, has a speaker key, which aids in the production of upper harmonics, raising the tone by a 12th.

The ever buree was designed in the 1970s and is usually heard as part of a regular Mongolian orchestra of nine players.

Bishgüür

A elaborately adorned metal trumpet, also known as a "shell trumpet" (bishgüür) in Mongolian. The Bighguur is a Mongolian reed instrument. Double-reed instruments, often known as 'trumpets,' are also popular in the Middle East, where it is known as a zurna in Turkey and Iran.

Suona (shawm) is the term used in China, surnay is used in Central Asia, and mizmar is used in Egypt and North Africa. This Mongolian bishgüür has a wooden body with seven front finger holes and is embellished with brass rings and blue and red coral. It ends with a huge copper and brass bell. The reed is a folded stem of marsh grass. For long phrases, the musician employs circular breathing by inserting the reed entirely into their mouth and pressing their lips against the disk above the pirouettes.

Mongolian Percussion Instruments

A variety of percussion instruments, such as those used to accompany dance and other activities in tropical and subtropical nations, were not frequently used in nomadic groups' livelihood, traditions, and practices. This could be due to concerns that these instruments will startle animals and livestock, as well as disrupt the mountains, rivers, and wildlife.

Tuur (Frame Drum or Shaman Drum)

A shaman drum with one head. Its frame is normally circular, but it can also be spherical. On one or both sides, the membrane is embellished with designs. Mongolian drums feature a big diameter and a powerful resonant sound. that will vibrate through the shaman's body, and the drum is commonly placed near the face or over the head so that the beat will resonate with great force through the shaman's head and upper body.

The most potent approach to induce trance is to beat the shaman drum. The shaman's drumming does not have a metronome-like consistency, but rather will slow down or speed up, become louder or softer depending on the shaman's mental condition at the time. Some shamans will demonstrate their communication with the spirit world by singing no interaction with the spirit world while remaining physically on earth Buddhism.

Denshig (Small Bells)

Two planished brass plates with a thin strap connecting the grips. During church services, a Lama beats two small plates against each other, making a sound comparable to that of a little bell.

They can only be found in Mongolia. The grips (knobs) of these two plainished brass plates are joined by a tiny band. During services, a lama bangs the two little plates together, making a sound comparable to the touch of a small bell but much softer and more lyrical.

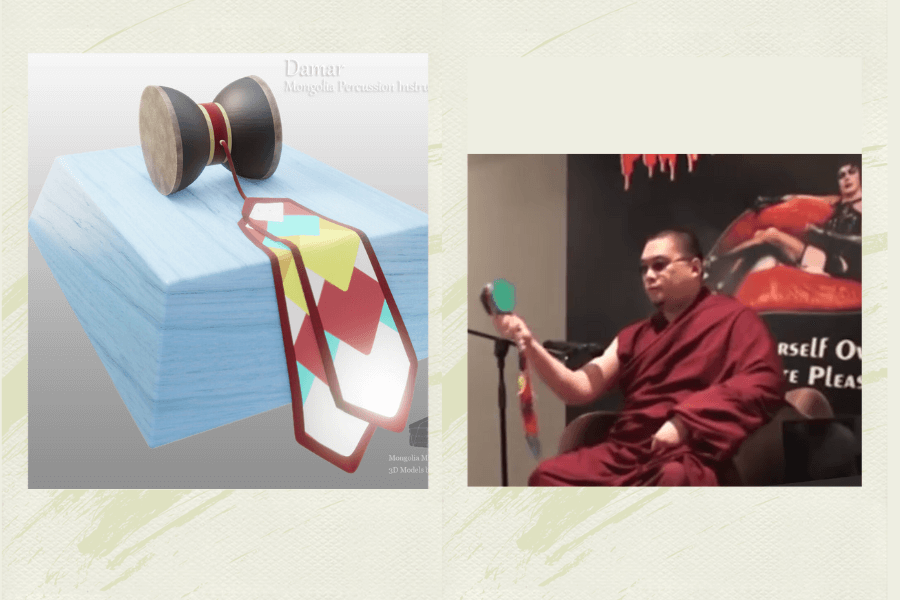

Damar

Small drums used in monasteries, having a hardwood shell resembling a coil. It has leather on both of its outside sides. In the center of the coil is a silk band with embroidery and two buttons linked to a thread. These two buttons are pressed on the stretched leather of this miniature drum by sliding back and forth.

Shigshuur (Shaman Rattle)

The Shigshuur, a sort of rattle, is also used by Mongolian music instruments - Shamans. It's fashioned of cow horn, with the pointed end carved to look like a raven's head. The Shigshuur is used to direct and send energy in one direction, with the rattle shaking like a raven pecking.

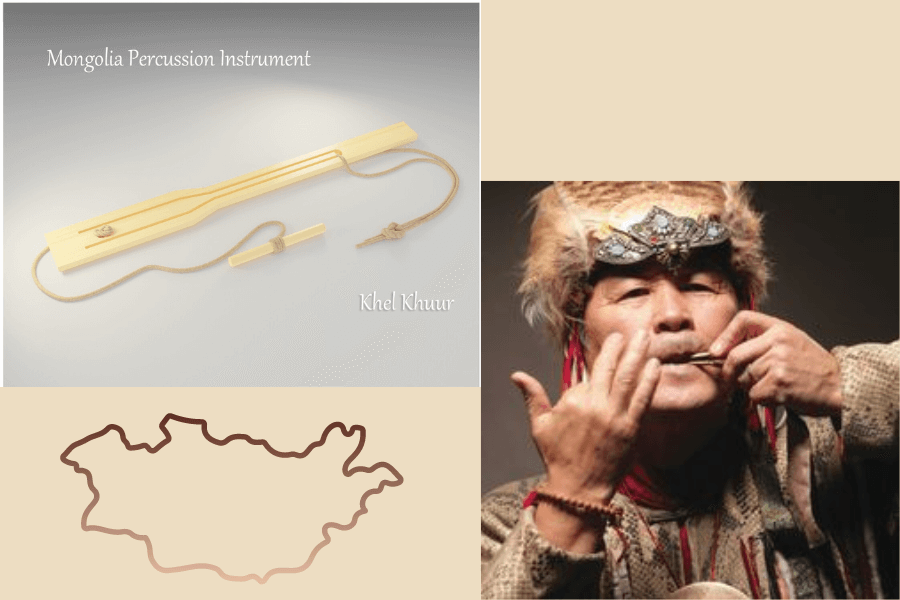

Khel khuur

The traditional Mongolian Jew's harp, made of wood or bamboo. Aman Khuur, a metal variation, is also played in the province of Khovd, for example.

Tsan

Cymbals come in both tiny and large sizes. With "straps" that are knotted inside

Other Percussion Instruments

Shighuur, Gongs, Bömbör (Drum), Kharanga (Gong), Denshig (Miniature Cymbals), Khonkh (Bells), Damar (Double-Headed Hourglass Drum), Duudaram (Gong-Chimes), Rattle, Shaman Bells, Khengereg (Big Drum)

All of these Mongolian traditional music instruments have been mainly used by the nomadic people. Music always attracts people’s attention. And the Mongols believe that such music can touch nature itself. Mongols always pround of their traditional music, and through our Mongolia packages, you will definately have a chance to immerse in Mongolian Traditional Music.